O days since it was DNS

Published on October 31, 2025

One of the most common terms you’ll hear during a cloud outage is DNS. Even the AWS outage on the 19th, Oct 2025 was reportedly triggered by DNS failures.

What happens when you try to visit a website?

User → Mysterious realm of the Internet → Server that hosts the website

On the Internet, machines are identified by a numeric address called an IP address (Internet Protocol address).

There are two broad types:

- Private IPs: Visible only inside a local/network.

- Public IPs: Reachable from the wider Internet.

Servers usually have one or more public IPs so they can be accessed. But most of us don’t type IP addresses into our browsers (maybe you’ve done it to reach a printer’s admin page). We use domain names instead. For example, when you open this blog, you see thuva4.com in the address bar. Your browser has to find the server’s IP address for that domain.

That’s where DNS comes in: a DNS server translates human-readable domain names into network-reachable IP addresses.

How does DNS work? First, two transport protocols to know:

- TCP (Transmission Control Protocol): Reliable, connection-oriented. It establishes a handshake and ensures accurate delivery - great for data transfer to and from servers.

- UDP (User Datagram Protocol): Faster but unreliable. It sends packets without guaranteeing delivery - useful for time-sensitive tasks where speed matters more than perfect delivery.

DNS typically uses UDP:

- The client sends a query asking for the IP of a domain.

- If a response arrives, the client uses the returned address.

- If not, it can retry or query another server.

No connection setup is required, and the process isn’t slowed by connection management.

Classic UDP DNS responses were once capped at 512 bytes, but EDNS(0) allows larger UDP payloads.

But what about TCP? DNS does use TCP in a few key cases. The most common is for zone transfers, which is how secondary servers get a full copy of all DNS records from a primary server. It also acts as a fallback if a query response is too large to fit in a single UDP packet, ensuring the data gets through reliably.

Zone transfers include AXFR/IXFR specifically. Also, many modern clients/resolvers support encrypted DNS variants like DoT (DNS over TLS), DoH (DNS over HTTPS), and DoQ (DNS over QUIC) - so DNS isn’t only “UDP on 53” anymore.

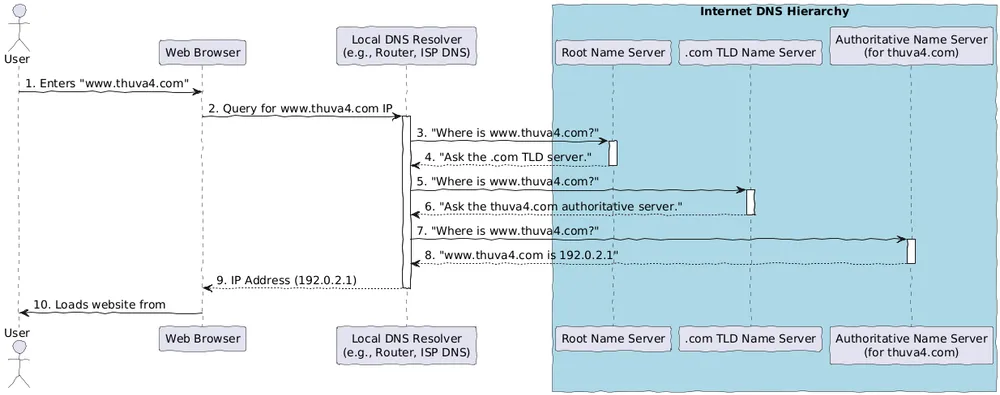

This lookup process is called DNS resolution. Because it’s impossible to keep the entire world’s mappings on one machine, DNS uses a hierarchical, recursive resolution pattern.

Example: Resolving www.thuva4.com

- Root name server → “I don’t know the IP, but ask the .com name servers.”

- .com TLD name server → “Ask the name servers responsible for thuva4.com.”

- Authoritative name server for thuva4.com → “

www.thuva4.comresolves to .”

Subdomains can be delegated to their own name servers via NS records (creating a separate zone), but many common labels (like www) are simply records that live inside the parent zone and aren’t separate delegations.

A Note on Speed: Caching (The Internet’s Short-Term Memory)

That resolution process looks slow, and it would be! If your browser had to do this every single time, the internet would grind to a halt.

The most important concept missing from that example is caching.

To prevent this slowdown, every server in the chain “remembers” the answer for a period of time (called a Time To Live, or TTL).

- The first time you visit, your local DNS resolver (like your router or Google’s 8.8.8.8) performs that full lookup.

- It then caches the answer (e.g.,

www.thuva4.com = <IP address>). - The next time you or anyone else using that resolver asks for that domain, it provides the answer instantly from its memory. This is why websites load instantly on the second visit.

Caching also happens in your browser and OS, and while it removes a DNS round-trip (often tens of milliseconds), overall page speed still depends on many other factors (TLS, TCP, content fetches, rendering, etc.).

A Note on Query Types: Recursive vs. Iterative

The process above is also a mix of two query types.

- Recursive Query: This is what your computer sends to its local resolver. It’s a “find this IP for me and give me the final answer” request.

- Iterative Query: This is what the resolver does. It “iterates” by asking the Root, which refers it to the .com server, which refers it to the

thuva4.comserver. Each step gives a new lead, not the final answer.