When Java's == Lies (But Actually Doesn't)

Published on November 23, 2025

Came across this StackOverflow question recently.

To be fair, I have always used .equals with boxed classes, it has become muscle memory, and IDEs are also really helpful with this.

Java provides 8 primitive types: boolean, byte, char, short, int, long, float, and double.

Each has a corresponding wrapper class (boxed type): Boolean, Byte, Character, Integer, Long, Float, and Double.

These wrapper classes provide additional functionality, methods, null support, use in generics—but they’re objects, not primitives. This distinction is where our mystery begins.

Let’s check what is happening.

When you write Integer a = 128; The Java compiler converts the code into the following bytecode:

Code:

0: sipush 128

3: invokestatic #7 // Method java/lang/Integer.valueOf:(I)Ljava/lang/Integer;

6: astore_1

7: returnJava automatically converts the primitive int to an Integer object through a process called autoboxing(invokestatic Integer.valueOf(I)).

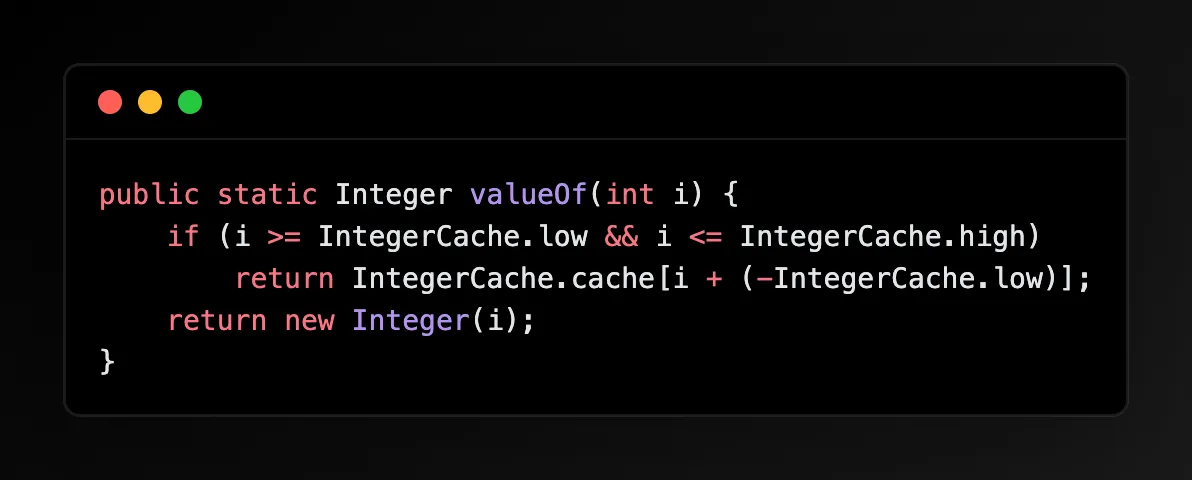

Let’s check what is happening inside Integer.valueOf:

You can see IntegerCache mentioned. What is it?

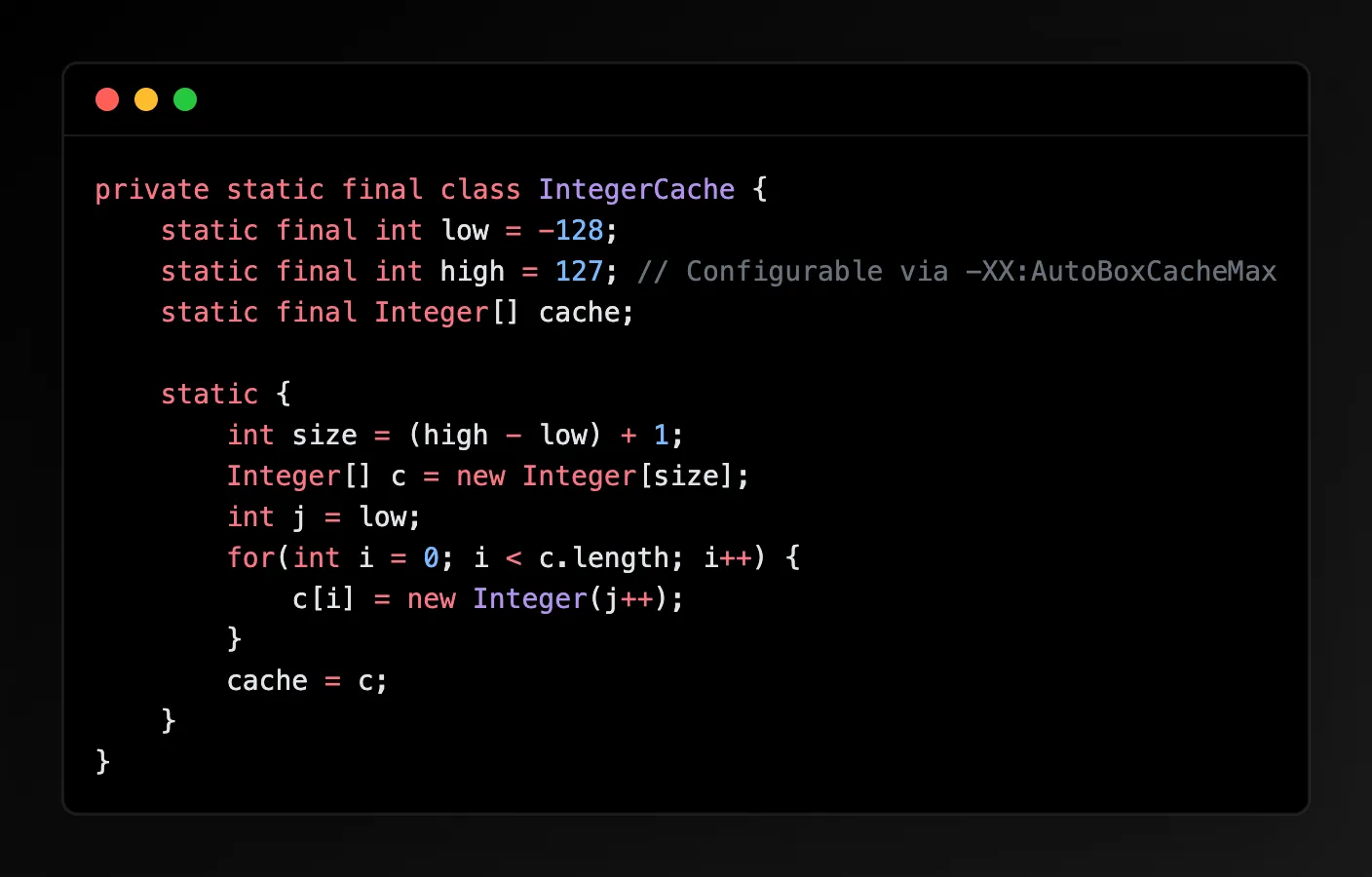

Full version can be checked here

This isn’t just an optimization trick, it’s required by the Java Language Specification (JLS 5.1.7). The spec mandates that boxing values of boolean, byte, char (≤ 127), and short/int between -128 and 127 must return the same cached instance. This ensures your code behaves consistently regardless of which JVM vendor you use.

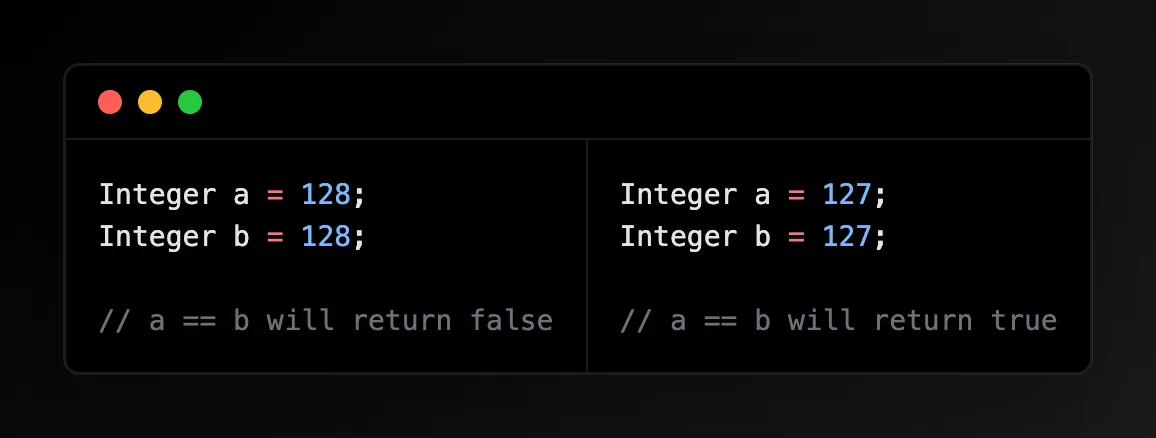

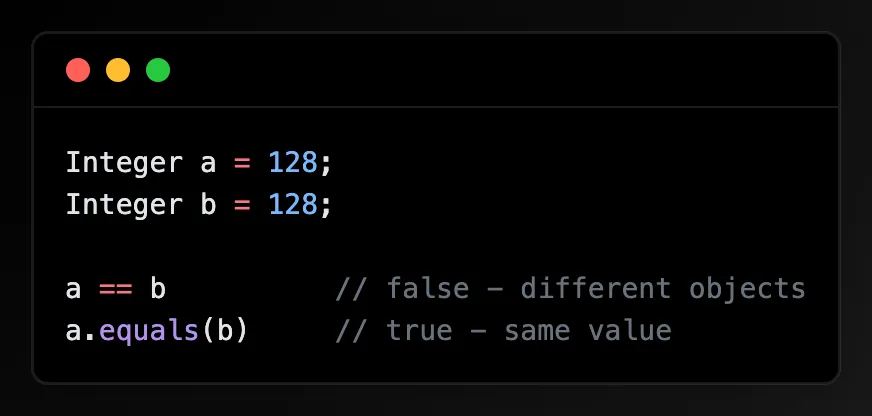

Now you can see the reason for the conflicting results in the comparisons.

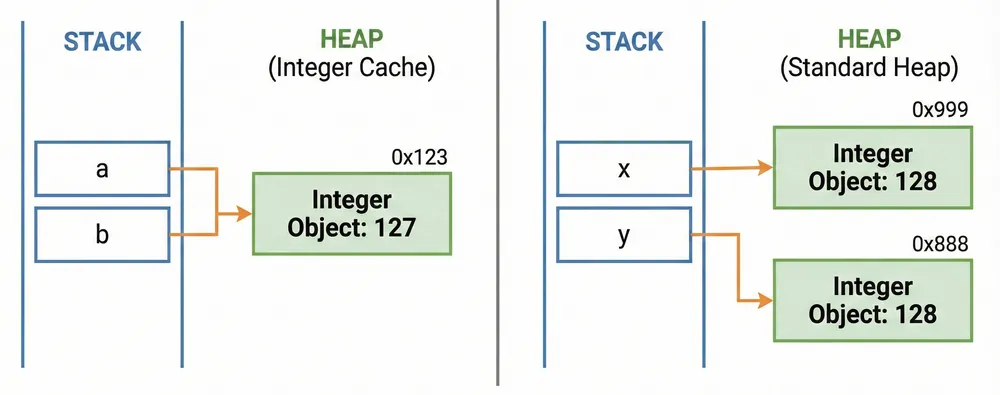

When you use == with objects, you are comparing object references, not the values themselves.

- Integer a = 127; Integer b = 127;: Both a and b reference the same cached Integer object from IntegerCache. So a == b returns true.

- Integer a = 128; Integer b = 128;: Both a and b are different Integer objects created outside the cache range. They have different references, so a == b returns false.

Important: This is exactly why you should always use .equals() when comparing objects in Java, not ==. The .equals() method compares values, while == compares references.

It is really amusing to see how much thought has been put into making these design decisions, even at a minuscule scale, and the impact it can have in real-world scenarios.

Want to dive deeper? If you found this interesting, I challenge you to look up String Internin (the String Constant Pool) on your own. It is another fascinating optimization in the JVM that behaves similarly but has its own unique quirks! Unlike Integer caching, which happens mainly through autoboxing, String literals are automatically interned by the JVM.

If this distinction between == and .equals() feels clunky, keep an eye on Project Valhalla. It aims to introduce Value Classes to Java. In the future, wrappers could become “identity-free,” meaning the JVM would treat them purely by their data—potentially making == compare values instead of memory addresses!